Breast cancer tumors disrupt the immune system remotely favoring their own growth

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine and collaborating institutions have identified a strategy cancerous tumors use to remotely disrupt the development of an immune response that could stop their growth.

Published in the journal Cell Stem Cell, the study shows in animal models that breast cancer tumors send molecular signals to the bone marrow, the birthplace of immune cells. The signals alter the natural environment of the bone marrow in such a way that it suppresses the response to fight back the tumor. Interestingly, these changes persist long after tumor removal.

The researchers also identified ways to accelerate the restoration of the normal conditions in the bone marrow after tumor removal, speeding up the recovery of the immune system. The findings warrant further research that could potentially lead to improved treatments for patients.

“Research has shown that breast cancer can have a significant impact in the body even before it metastasizes or spreads to other organs. For instance, tumors can remotely disrupt the ecosystem inside the bone marrow, leading to an immune response that does not attack the tumor but favors its growth instead,” said corresponding author Dr. Xiang H.-F. Zhang, William T. Butler, M.D., Endowed Chair for Distinguished Faculty and interim director of the Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center at Baylor. “To understand how this happens, we characterized the organization of the bone marrow in breast cancer animal models before the tumor had metastasized.”

The team found that even small tumors can affect the body profoundly as they trigger multiple changes in the bone marrow.

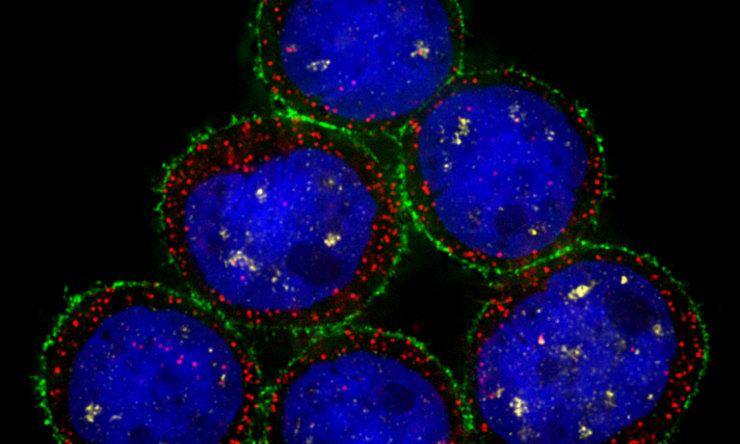

“Breast cancer tumors promote the over production of bone marrow cells called osteoprogenitor cells, which will later contribute to the formation of new bone,” said first author Dr. Xiaoxin Hao, postdoctoral associate in the Zhang lab.

In addition, other cells, the progenitors of cells that give rise to immune cells, also grow in numbers. Importantly, these progenitors also change their typical location within the bone marrow, relocating near the osteoprogenitor cells and establishing a new cell-to-cell communication with these cells, particularly with a subset called granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs).

“We think that this osteoprogenitor-GMP communication is key, because GMPs give rise to neutrophils and monocytes, immune cells that have long been known to accumulate in some breast cancer tumors in patients and breast cancer mouse models and help promote tumor growth by suppressing the anti-tumor immune response,” Hao said.

The researchers were surprised to find that after they removed the tumor, which they considered the source of the problem, the disruption of the bone marrow did not recover immediately.

“We observed this in animal models,” Hao said. “In some patients, we have seen that even more than 40 weeks after removing the tumor, increased numbers of neutrophils remain in their blood, which is clinically relevant.”

In some cases, tumor removal is followed by immunotherapy, which relies on an intact immune system for its success. “Our findings suggest that at least in some patients the immune system is still compromised after removing the tumor, likely reducing the beneficial effects of immunotherapy,” said Zhang, a member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center and a McNair Scholar.

In addition, the findings have implications for metastasis. Metastasis may arise years or even decades after the tumor has been surgically removed seeded by residual cancer cells left behind after the surgery. “An immunosuppressive effect lingering after the surgery may create an environment favorable for the residual cancer cells to proliferate and metastasize,” Hao said.

The researchers also identified protein MMP-13 as an essential mediator of the crosstalk between osteoprogenitor cells and GMPs. “We showed that if we eliminate or inhibit MMP-13, we can accelerate the recovery of the immune system and restore the efficacy of immunotherapies,” Hao said.

“Our findings suggest a new modality of treatment that is very different from the current strategies. It’s not targeting the cancer cells, it’s not targeting immune T cells that attack cancer cells, it’s targeting the whole organism. It’s trying to remove a kind of shadow cast over the entire immune system,” Zhang said. “This is just the beginning of a series of studies on how tumors alter the whole body. Our findings support continuing our research on this path, and we hope it will lead to the identification of improved treatments for cancer patients.”

Other contributors to this work include Yichao Shen, Nan Chen, Weijie Zhang, Elizabeth Valverde, Ling Wu, Hilda L. Chan, Zhan Xu, Liqun Yu, Yang Gao, Igor Bado, Laura Natalee Michie, Charlotte Helena Rivas, Luis Becerra-Dominguez, Sergio Aguirre, Bradley C. Pingel, Yi-Hsuan Wu, Fengshuo Liu, Yunfeng Ding, David G. Edwards, Jun Liu, Angela Alexander, Naoto T. Ueno, Po-Ren Hsueh, Chih-Yen Tu, Liang-Chih Liu, Shu-Hsia Chen, Mien-Chie Hung and Bora Lim. The authors are affiliated with one or more of the following institutions: Baylor College of Medicine, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center-Houston, University of Hawai’i Cancer Center, Medical University Hospital and Houston Methodist Research Institute.

The study is supported by the U.S. Department of Defense DAMD W81XWH-16-1-0073 (Era of Hope Scholarship), NCI CA183878, NCI CA251950, NCI CA221946, NCI CA227904, NCI CA253533, DAMD W81XWH-20-1-0375, Breast Cancer Research Foundation and McNair Medical Institute. Further support was provided by NIH grants (S10OD023469, S10OD025240, P30EY002520, CA125123 and RR024574) and CPRIT grants RP200504 and CPRIT-RP180672.