What Is a Brain Aneurysm?

A brain aneurysm is an area of weakness in a brain blood vessel that over time can grow larger and thinner. Aneurysms are dangerous because they can grow and eventually rupture allowing blood to leak out of the vessel. When aneurysms bleed, the blood accumulates in the fluid space under the brain and this is called a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Aneurysms that bleed are life-threatening and should be treated urgently as it is a life-threatening emergency. Brain aneurysms that are discovered before they have bled are often treated to prevent rupture.

Brain aneurysms are relatively common. Approximately 10–12 million people in the U.S. have brain aneurysms and about 27,000 new aneurysms are discovered each year (Brisman, Song & Newell, 2006). However, not all aneurysms are high risk to rupture and it is important to speak with a cerebrovascular neurosurgeon about your particular aneurysm.

The cerebrovascular neurosurgeons at Baylor Medicine and Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center in Houston, Texas, specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of brain aneurysms and other brain blood vessel disorders. Our doctors have national reputations as leaders in the field of aneurysm treatment. Each brain aneurysm is different and our doctors provide great expertise managing these potentially dangerous lesions.

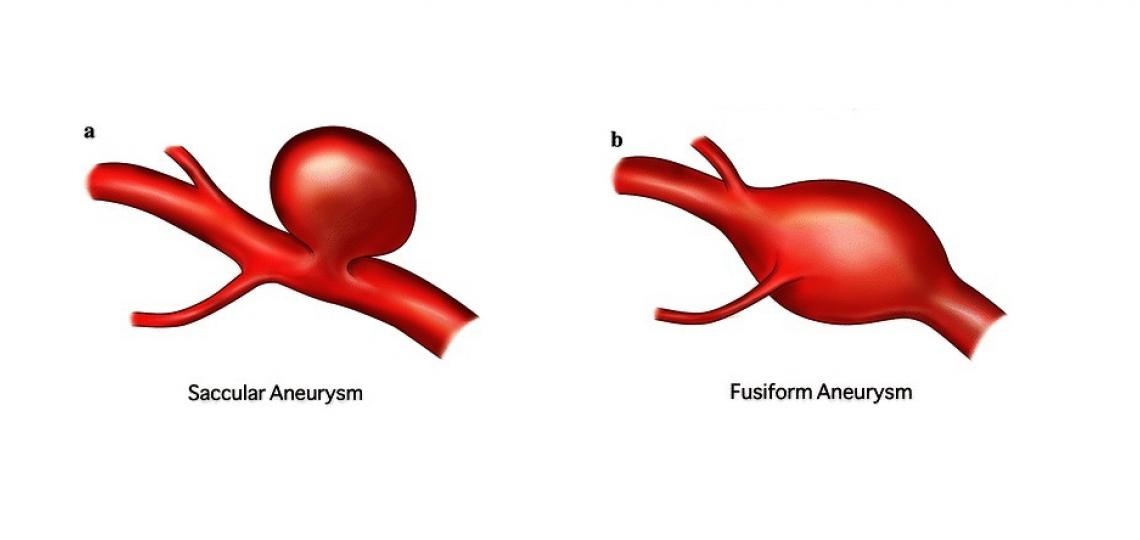

Figure 1a: Saccular aneurysm. Figure 1b: Fusiform Aneurysm

What Causes Brain Aneurysms?

In most cases, the reason why aneurysms form is unclear. Some things are known to contribute to brain aneurysm formation, including cigarette smoking, chronic high blood pressure, chronic alcohol use, illicit drug use, and some rare genetic blood vessel diseases.

Why Are Brain Aneurysms Dangerous?

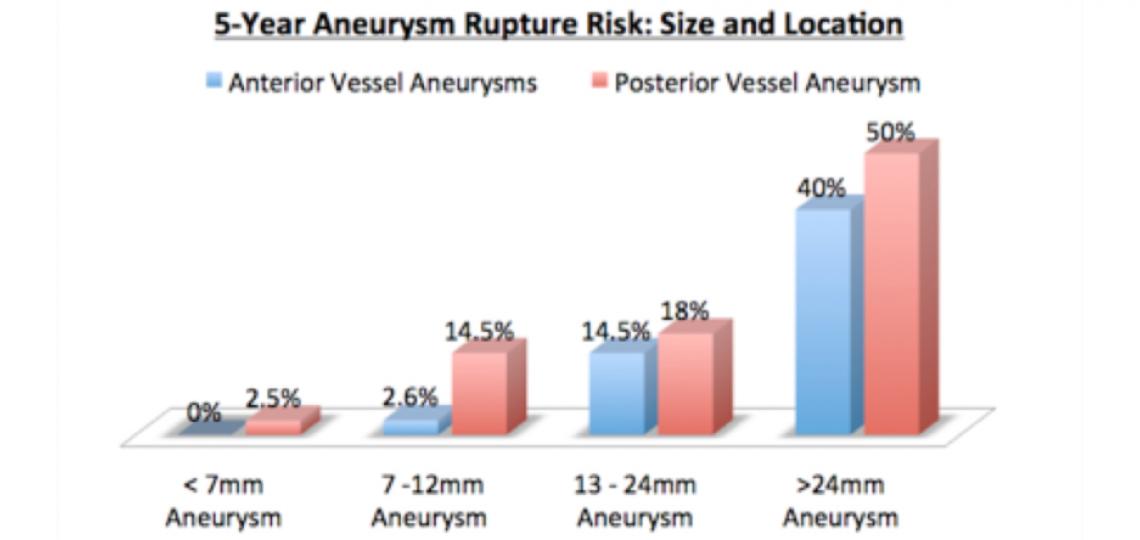

Size and location are the most important factors that determine the likelihood that an aneurysm will rupture. Small aneurysms (less than five millimeters in size) are unlikely to rupture and are often not treated at all unless they begin to grow. The larger an aneurysm is, the higher the chance it will bleed (Table 1) and the more likely it will need treatment. However, certain aneurysms with abnormal shapes or certain vessel locations may need treatment at small sizes.

The location of an aneurysm is also important. Aneurysms on blood vessels located in the back half of the brain (vertebral arteries, the basilar artery, and the posterior communicating artery) are at higher risk of bleeding than aneurysms found on blood vessels in the front half of the brain (the carotid artery, the middle cerebral artery, and the anterior cerebral artery). Other factors that are thought to increase the likelihood of a rupture include aneurysm growth, multiple aneurysms, prior aneurysm rupture, symptoms of aneurysm leak or nerve compression, irregular aneurysm wall outpouchings, and aneurysm ruptures in multiple family members.

Table 1. The chance of rupture for a given aneurysm depends on its size and location on brain blood vessels. Larger aneurysms are higher risk for bleeding. Aneurysms on the vessels at the front of the brain (anterior circulation – blue bars) are less dangerous than aneurysms on the back part of the brain (posterior circulation - red bars).

|

Aneurysm Size |

Anterior Rupture Risk |

Posterior Rupture Risk |

|---|---|---|

|

< 7mm |

0% |

2.5% |

|

7 - 12 mm |

2.6% |

14.5% |

|

13 - 24mm |

14.5% |

18% |

|

> 24mm |

40% |

50% |

Symptoms

Most brain aneurysms are silent until they bleed. However, sometimes a small “leak” of blood from the aneurysm can produce certain warning symptoms, such as nausea and headaches, days to weeks before a major rupture. Classic symptoms of aneurysm rupture and bleeding around the brain (subarachnoid hemorrhage) include but are not limited to the following:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sudden severe headache, often described as "the worst headache of my life"

- Confusion or abnormal sleepiness

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Dilated pupil of the eye

Because ruptured aneurysms are life-threatening emergencies, if someone demonstrates these symptoms, medical help should be sought immediately!

Diagnosis

Aneurysms are identified through the use of brain vessel imaging techniques. The most common tests used to evaluate a brain for aneurysms include:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Angiogram (MRA) – Uses magnetic fields to create images of the brain and the brain’s blood vessels.

Computed Tomography Angiogram (CTA) – Uses multiple x-ray images taken from different angles to produce cross-sectional pictures of the brain and brain blood vessels. To see blood vessels more accurately with CT scans, contrast dye must be injected into the patient’s veins through an IV, usually in the arm.

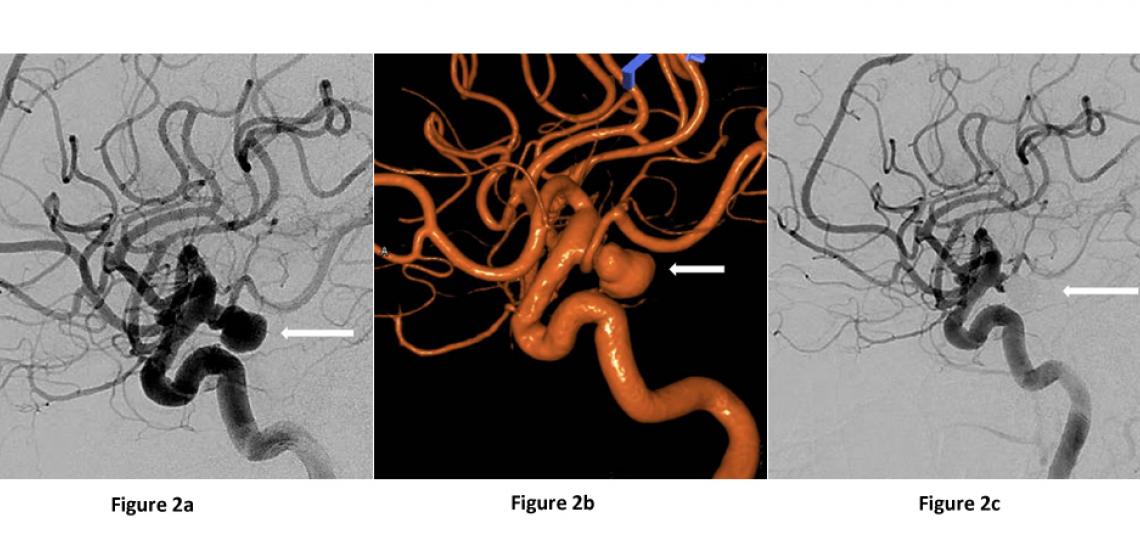

Cerebral Angiogram (Digital Subtraction Angiography) – Small tubes are placed inside the arteries of the leg where they are advanced into the arteries of the neck using x-ray guidance. Dye is then injected through the tube and flows with the blood through the neck arteries into the brain blood vessels. This technique gives doctors the highest quality images of the neck and brain blood vessels (Figures 2a-c).

Figures 2a and 2b: Lateral view of the same ruptured left posterior communicating artery aneurysm (arrow) on a cerebral angiogram before aneurysm treatment. Figure 2c: After treatment with aneurysm coiling.

Treatment

There are many factors that go into the decision to treat a brain aneurysm. Your cerebrovascular neurosurgeon will help guide you through the different options to make the best decision possible for you and your individual case. Some aneurysms are best watched and not treated while others need treatment to prevent possible rupture. There are two general techniques to treat brain aneurysms: surgical clipping and endovascular treatment.

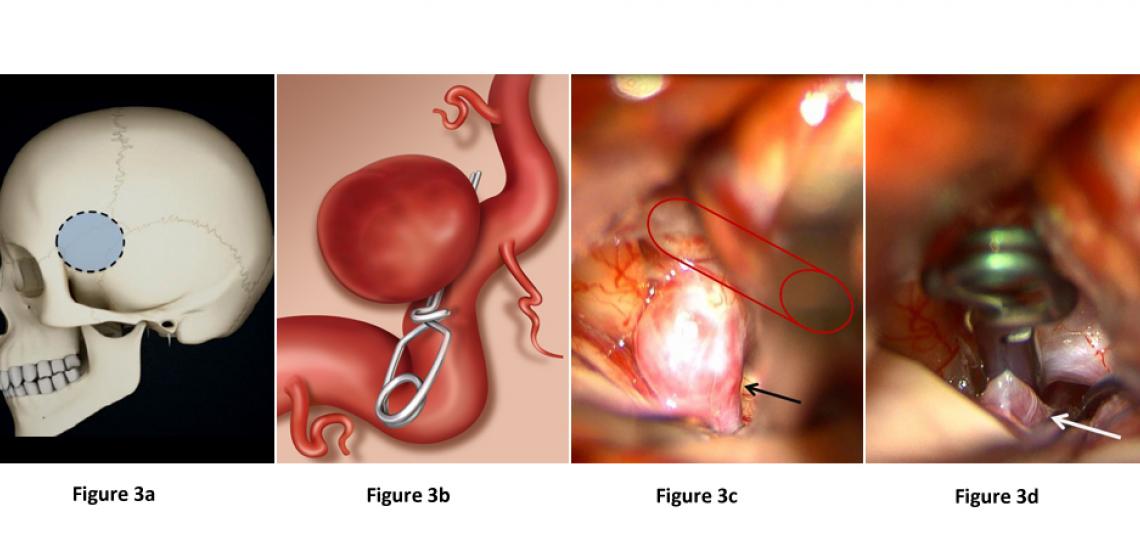

Surgical Clipping

Surgical treatment for aneurysms involves opening the skin and bone over the surface of the brain (Figure 3a). The surgeon carefully dissects under the brain or between the lobes of the brain and places a metal clip across the “neck” or base of the aneurysm (Figure 3b). The clip blocks blood from entering the aneurysm, preventing it from bleeding while keeping the normal artery open.

Figure 3a: The outline of a typical craniotomy for aneurysm clipping. Figure 3b: Illustration of an aneurysm clip placed across the neck of an aneurysm, blocking blood flow into it while keeping the normal vessel open. Figure 3c: Surgical image showing a right carotid artery (red outline) aneurysm (arrow) before aneurysm clipping. Figure 3d: The same surgical image immediately after clip placement on the brain aneurysm, curing it.

Endovascular Treatment (Neurointerventional Treatment)

Aneurysms with favorable locations and shapes can be treated from inside the blood vessel via small catheters and tubes advanced into the brain vessels using x-ray guidance. Once in the brain vessels, these tubes can be used to deliver therapies to close aneurysms. The three most common ways to treat an aneurysm from inside the vessel are:

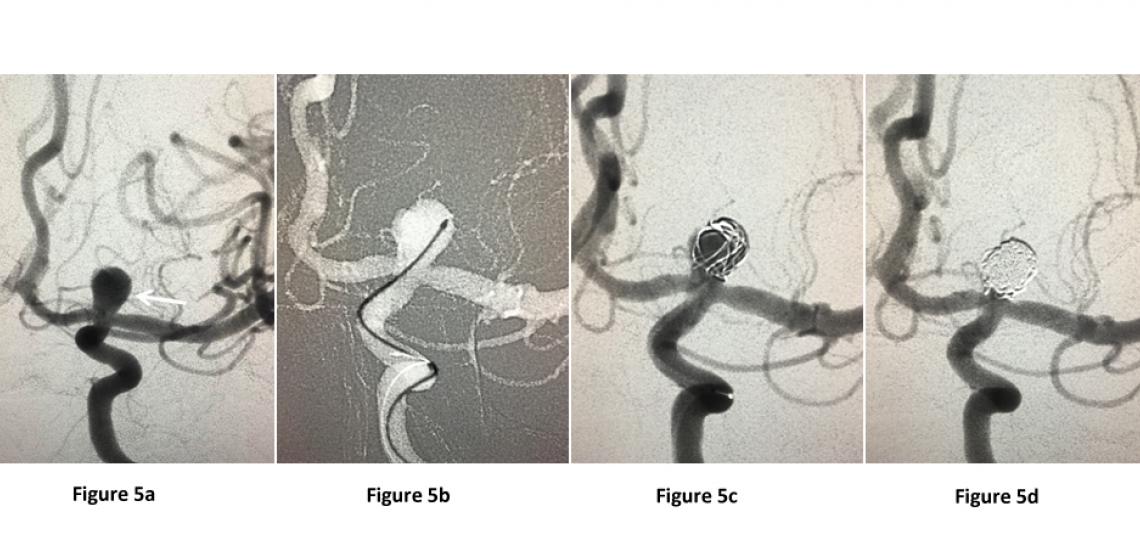

Endovascular Coiling – Small metal coils are pushed through the tubes and delivered into the aneurysm, thereby blocking blood from entering and preventing future rupture (Figures 4 and 5).

Endovascular Stent-Assisted Coiling – A small metal stent is placed in the vessel across the base of the aneurysm to protect it from the coils that are delivered into the aneurysm through the tubes.

Endovascular Flow Diversion – A metal stent with narrow holes is placed across the base of an aneurysm. The stent diverts blood flow away from the aneurysm and encourages it to stay in the vessel. Over several months, the blood in the aneurysm clots due to slow flow and the aneurysm heals, but the normal vessel stays open. This technique is often used for very large aneurysms or aneurysms that are difficult to treat with coiling or surgery (Figure 6).

Figure 4. A diagram of the steps of endovascular aneurysm coiling showing: (a) an aneurysm prior to treatment (b) a catheter placed inside the aneurysm (c) coils being pushed through the catheter to fill the aneurysm and (d) the final state after aneurysm after coiling with the aneurysm now filled with metal coils and the main vessel open.

Figure 5a: Brain angiogram demonstrating an aneurysm at the top of the left carotid artery. Figure 5b: A small catheter is advanced into the aneurysm. Figure 5c: Coils (small metal wires) are placed through the catheter inside the aneurysm and detached there until blood flow into the aneurysm is fully blocked and protected from rupture (Figure 5d).

Figure 6. Front view (a) and side view (b) of a large left sided carotid artery aneurysm. After placement of a flow diverting stent device, the aneurysm slowly shrank and the vessel healed. Six months after the procedure, the aneurysm is cured (c, d). The three-dimensional angiogram (e) shows the flow-diversion device lining the walls of the vessel.

Helpful Links

References

Brisman JL, Song JK, Newell DW. Cerebral aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:928-39. PMID 16943405.

The International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet. 2003;362:103-10. PMID 12867109.

Credit

Credit