Bioterrorism agents are pathogenic organisms or biological toxins that are used to produce death and disease in humans, animals, or plants for terrorist purposes. These agents are typically microorganisms found in nature, but it is possible that they could be modified to increase their virulence, make them resistant to current antibiotics or vaccines, or to enhance the ability of these agents to be disseminated into the environment.

Terrorists may find biological agents to be an attractive alternative to conventional weapons because of their relatively low costs, their relative accessibility, and the relative ease in which they could be produced, delivered, and avoid detection. Their use, or even threatened use, is potentially capable of producing widespread social disruption.

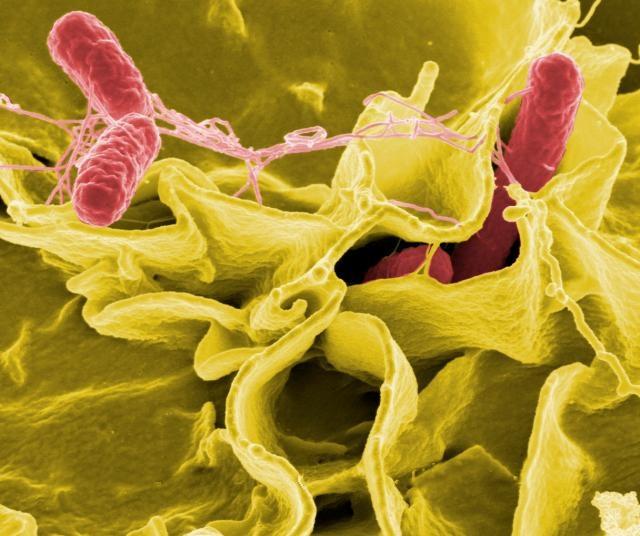

The concept of using biological agents in warfare is not new. There are many examples throughout recorded history - even as early as the 6th century BC when the Assyrians reportedly poisoned wells of their enemies with the fungus rye ergot. In the 1700s during the French-Indian War, it is suspected that the British gave blankets that had been used by smallpox victims to the Native Americans, resulting in decimation of the native population. More recently, in 1984, followers of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh contaminated salad bars in Oregon with Salmonella in an attempt to influence a local election (although hundreds were sickened, this attack did not impact the election).

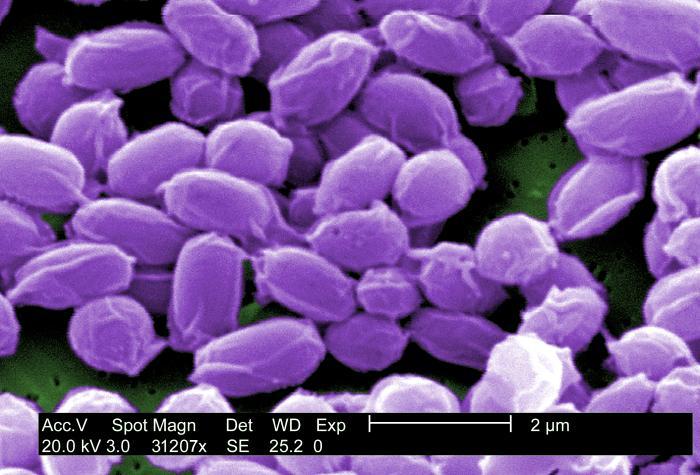

As a result of the terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C on Sept. 11, 2001 and the dissemination of anthrax through the United States Postal Service shortly thereafter, there has been renewed and urgent attention focused on the possibility of additional terrorist acts involving biological agents. The U.S. government has responded by expanding resources and effort into biodefense research. Much of this work is directed by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases component of the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, along with other agencies including the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

As technologies for genetically modifying organisms have advanced and become more accessible, it has become easier and less expensive to alter the genetic makeup of viruses and bacteria. The potential for misuse of synthetic biology capabilities increases and expands the threat of bioweapons. The tools could be used for the creation of pathogenic microorganisms or the modification of existing microorganisms to make them more dangerous.

Among the areas of greatest concern are the potential for the reconstruction of known pathogenic viruses using information on their genetic sequences (e.g., the 1918 pandemic flu virus) or the alteration of existing bacteria to make them more dangerous (e.g., by making them resistant to existing antibiotics). Another concern is the potential to engineer a microorganism that releases harmful biochemicals within the human body. Other possible risks include alterations to the human host, such as modifications to the human microbiome or the human immune system.

Classification of Bioterrorism Agents

The CDC and NIAID, in conjunction with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, evaluate the potential threat from various microorganisms and toxins and classify them into three categories.

Category A consists of the agents that are considered the highest risk, and much of the biodefense research effort is directed towards these agents. Included among Category B agents are ones that could conceivably threaten water and food safety. Category C includes pathogens that are considered emerging infectious disease threats and which could be engineered for mass dissemination.

To determine the risks from various agents, the CDC considers their effect on human health, the degree of contagiousness or method of transfer to humans, and the availability and effectiveness of vaccines and therapies to prevent and treat illness.

The level of threat from specific agents is reviewed and revised periodically. New high-risk pathogens may be added to the list as they are discovered. It is also possible that the relative level of threat could change. For example, if an effective vaccine is developed against a particular agent, its level of threat would decrease, whereas if an agent becomes resistant to current therapies, its level of threat could increase.

The classification into Categories A, B, and C is based on:

- The ability of the agent to be disseminated

- The mortality rate of the agent

- The actions required for public health preparedness

- The capability of causing public panic

| Category A | Category B | Category C |

|---|---|---|

| Pose the highest risk to national security | Pose the second highest risk to national security | Emerging pathogens that could be engineered for mass dissemination |

| Can be easily disseminated or transmitted from person to person | Are moderately easy to disseminate | Are easily produced and disseminated |

| Have potential for high morbidity and mortality rates and major health impact | ||

| Require special public health preparedness actions | Require enhanced diagnostic capacity and disease surveillance | Are available |

| Have potential to cause public panic and social disruption |

| Category A | Category B | Category C |

|---|---|---|

| Botulism | Hendra | |

| Cholera | ||

| E. coli O157:H7 | ||

| Hantavirus | Hepatitis A | Nipah |

| Lassa | Ricin toxin | Prions |

| Marburg | Salmonella | Rabies |

| Plague | Typhus fever | |

| Yellow fever | Tickborne encephalitis | |

Biodefense Research

Research efforts in biodefense are directed at:

- Understanding the basic biology of potential bioterrorism agents

- Understanding the interaction between the human immune system and these microorganisms

- Developing and improving drugs and vaccines that are effective against bioterrorism agents

- Developing tools to quickly and accurately diagnose diseases caused by these agents

- Establishing resources and biosafety laboratories to facilitate biodefense research

Research at Baylor College of Medicine

Researchers in the Department of Molecular Virology and Microbiology have studied and continue to investigate a number of pathogens that present a potential risk for use in bioterrorism. Included among them are the Category A agents - anthrax, dengue, Ebola, smallpox, and tularemia - as well as Category B and C agents such as chikungunya, influenza, and Zika. The research encompasses investigations into the basic biology of these agents, their interactions with the immune system, as well as the development of vaccines and tools to study and combat these agents.

Notably, MVM is home to a Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit (VTEU), one of only nine such sites nationwide. The VTEU is funded by the NIAID component of the NIH and provides the infrastructure to conduct phase I and II clinical trials of candidate vaccines and other biologics for protection against biological weapons and emerging infectious diseases.

Glossary

Learn more about some of the technical terms found on our glossary of terms page.

Credit

Credit