About the Center

The Texas Children's Microbiome Center, part of the Human Microbiome Project Consortium, translates new knowledge about the human microbiome in different areas of medicine by pursuing metagenomic and microbiome research related to the care of women and children.

As part of Human Microbiome Project Consortium and in collaboration with the Bioinformatics Research Laboratory, the Human Genome Sequencing Center and the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research, it is strategically placed to partner with a variety of departments and centers at Texas Children's Hospital as well. The Microbiome Center provides complete service and support from initial study design and sample collection to final metagenomic analysis.

Currently, faculty in the center are working to characterize the intestinal microbiome and the nature of the core microbiome in healthy children. In addition, they are studying the changes in the metagenome that may be associated with disorders of mucosal inflammation and recurrent abdominal (visceral) pain. The tools for analysis include next-generation DNA sequencing, quantitative PCR and high density microarrays to study shifts in the metagenome and human-associated microbial communities.

Studying Microbial Communities in Children

Humans are host to an array of microbial communities that have adapted to a variety of body sites. The Human Microbiome Project has put forth a significant effort to characterize the composition of these microbial communities in healthy adults.

At the Texas Children’s Microbiome Center, we are comparing microbial communities present in healthy and disease states of children. Identifying key differences in these communities will lead us to translational research that will forge new therapeutic and diagnostic tools.

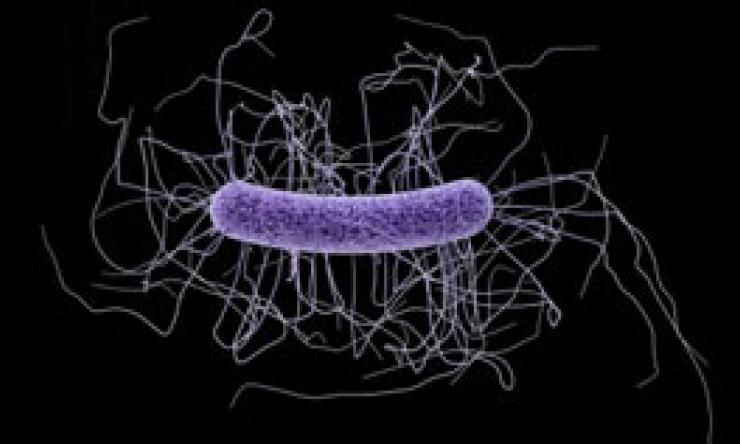

Next-generation probiotics might join the fight against gut bacterial infections

Clostridium difficile infections are the most common cause of diarrhea associated with the use of antibiotics. If these bacteria attempt to invade the human gut, the ‘good bacteria,’ which outnumber C. difficile, usually prevent them from growing.